– Thomas Sigler and Rory Crofts –

The motivation to write this paper was twofold. In part, it was personal curiosity. Between the two of us, we have lived in several tax havens, including Bermuda, Luxembourg, and Panama. As one might assume, the day-to-day economic activities of these places differ considerably from those in the rest of world. Their high-rise office towers most often contain banks, but not the sort that one would normally open an account with. In Bermuda, most residents have some tie to the captive insurance industry; Luxembourg’s ‘fiduciaries’ occupy prime real estate near the city center, but are often characterised by vacant offices; Panama is reputed to have more lawyers per capita than New York. As geographers, our intellectual curiosity led us to investigate these places in further depth.

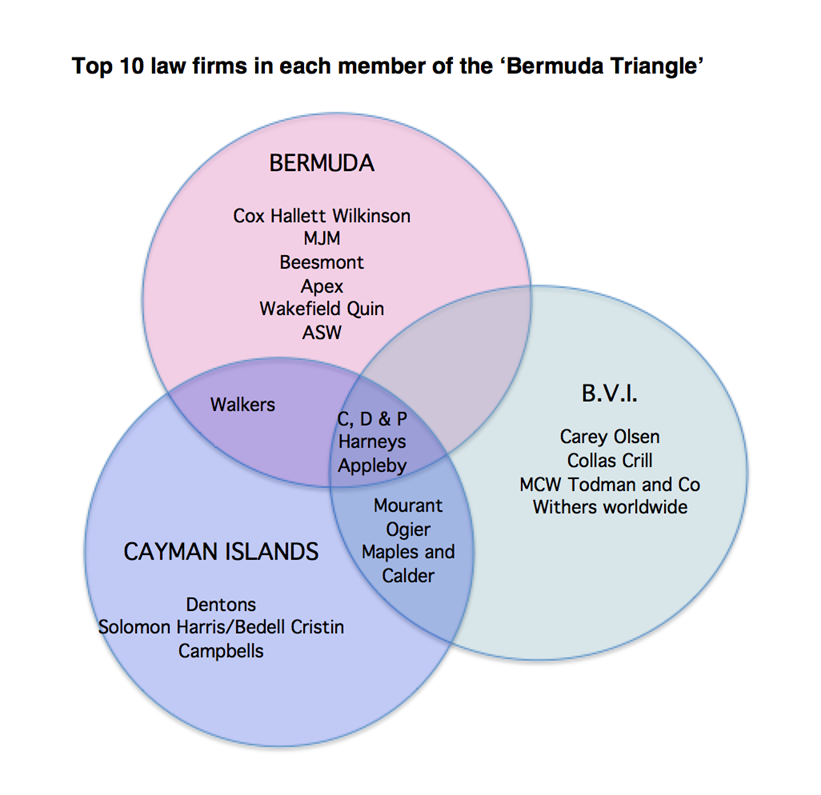

The second reason we wrote this paper was to apply network analysis to understanding the interrelatedness of tax havens. Law firms, banks, and other advanced services providers often pride themselves on offering a broad range of services (e.g. brokerage, domiciling) through a network of local affiliates. Panamanian firms might have affiliates or branch offices in Luxembourg, just as Irish firms may have offices in Jersey or Bermuda. The figure below illustrates this point based on common law firms in the ‘Bermuda Triangle’.

Just as ‘mainstream’ producer services are networked through world cities (e.g. New York, Hong Kong), there is a parallel network of places within the global financial circuitry that is perhaps equally well connected. These relations, in this case proxied by common services offered by firms, were the topic of our paper. We used network analysis for the simple fact that we conceptualised the complex set of relationships between offshore financial centers as a network. As tax havens are by definition multi-national operations, we took common services as the ‘link’ between two places. For example, if both Liberia and Panama specialise in ship registry, as they do, it was assumed that there must be a common link between them, which could take the form of information sharing, common legislative frameworks, etc.

The findings run counter to the narrative that tax havens are ‘rogue’ operators. The most central sub-network grouping (the Netherlands, Ireland, Luxembourg) finds itself within the European Union, and many of the most significant tax havens are British Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories, rather than autonomous island nations. Another interesting finding was the existence of ‘cliques’, which are defined in network theory as sub-network groupings of fully interconnected nodes. These manifested along both functional lines – with Panama, Liberia, and Cyprus as shipping hubs – as well as geographical lines – with the ‘Bermuda Triangle’ of Bermuda, Cayman Islands, and BVI functionally interdependent.

It is likely that tax havens will continue to be a key focus of scholarship. Financial geography can provide a useful lens in this regard and future studies should continue to focus on tax haven network relations.

Photo of Luxembourg (Thomas Sigler)

Photo of Bermuda (Rory Crofts)